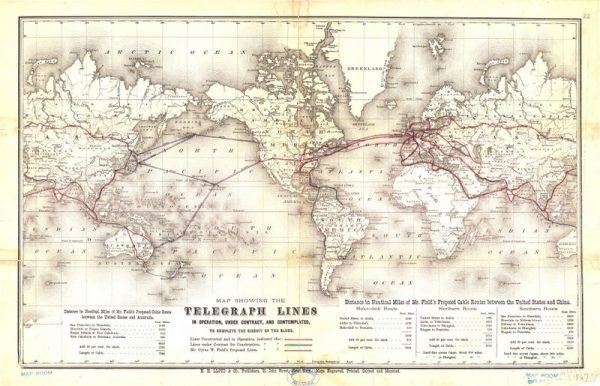

In 1881, the telegraph was metaphorically described as the nerves of the world, with the roads being its veins. At this juncture, the expansive sands of Africa and the icy expanse of the Arctic were the only regions yet untouched by the telegraphic grid. These pulses of energy, traversing across the globe, marked humanity’s initial foray into the information era.

The book ‘The Wonders of Electricity’, published the same year, provides a fascinating perspective on the telegraph, highlighting the challenges associated with this cutting-edge technology. A case in point: a London omnibus driver who tragically lost his life to a stray wire. Also, residents living near these wires feared they might act as lightning magnets.

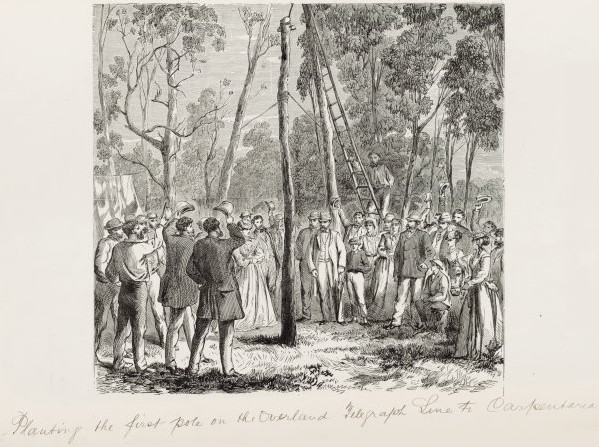

The book talks about the exotic challenges faced while expanding telegraphy worldwide. Buffalos, tigers, bandicoots, and monkeys were all potential disruptors of this global endeavour. Moreover, other complications ranged from the locals using telegraph posts as firewood, to corrupt officials, and bizarrely, certain Spanish communities believing in the need to grease the telegraph wires with the fat of deceased children.

Even with its colonial perspective, the book provides a captivating glimpse into the awe inspired by the first transnational connections. One instance was the inaugural submarine cable laid in 1850 between the UK and France. Despite functioning for only a few hours, its discovery by a fisherman, mistaking it for an unusual type of seaweed, added a layer of intrigue.

The next milestone came in 1858 with the first cable linking Ireland (then part of the United Kingdom) and Newfoundland in the United States. This achievement was marked by the exchange of greetings between the US President and the British Queen. However, the advent of the Civil War soon diverted focus from transatlantic communications.

When this book was penned, the telegraphic network had extended to include half a dozen cables from the UK to the USA, one from Portugal to Brazil, three cables to India, and an under-construction link to the war-ridden South Africa. This was a degree of interconnection never seen before.

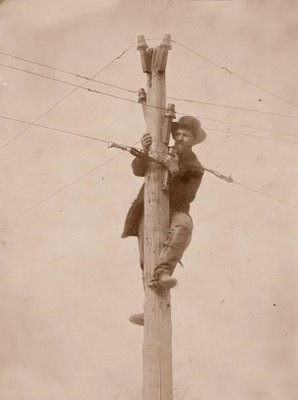

The narrative then moves on to the technical hurdles faced, like the selection of copper over iron for the wires, despite its higher cost, and the complexity of the wire structures. The bizarre challenges of oceanic creatures, such as zoophytes, spike-backed sunfish, and toredo worms, also had to be considered when designing the submarine cables.

This historical account may appear amusing now, but it’s important to remember that these telegraph wires heralded a global shrinkage, an achievement we tend to overlook in today’s internet era. The infrastructure of copper wires, described as the world’s nerves, remains crucial today.

Ending on a rather prophetic note, the chapter highlights the mind-boggling speed of thoughts that would circumnavigate the world once a cable linked San Francisco to Japan. The author then speculates about a future invention superseding these wire and cable networks – a prediction that has come true with the advent of radio and satellites.

“When a cable is once laid from San Francisco to Japan, we shall have a girdle around the world, on which it will be slow work for thought to travel in forty seconds. And then – who knows? There may come some other amazing discovery, to render useless all this cobweb of wires and cables.”